Field Notes: Tackling Multidimensional Poverty

In 1942, William Beveridge wrote a report that took Britain by storm, identifying the “Five Giant Evils” of “squalor, ignorance, want, idleness, and disease” and ways for the British government to address them. Inspired by this multidimensional understanding of poverty, Brookings Institute’s Richard Reeves, Edward Rodrigue, and Elizabeth Kneebone authored a recent report, Five Evils: Multidimensional Poverty and Race in America, that looks at how people experiencing low income also experience compounding factors such as low education, lack of access to healthcare, resource-poor neighborhoods and jobless households. These factors, which tend to cluster differently for white, black and Hispanic Americans, result in fewer opportunities, increased risks, and social isolation:

Lack of education inhibits life chances, earning opportunities, and economic security. …. Lacking insurance exposes people to greater health and financial risks in the event of illness. Research also suggests that the uncertainty associated with uninsurance creates ongoing psychological stress for families. … Living in a high-poverty area puts people at a disadvantage, above and beyond their own household’s income-poverty status, because of local factors like the quality of schools, social capital, job connections, and crime. … Employment brings advantages above and beyond current income, including the prospect of a higher income in the future and a sense of purpose and structure. Of course not all adults need to have a job—especially in a household with caring responsibilities—but it is better to be in a working family than a jobless family, even apart from the obvious economic implications.

Of course poverty is about a lack of money. But it is not only about that. … Poverty as a lived experience is often characterized not just by low income, but by ill health, insecurity, discomfort, isolation, and lack of agency. In practice, of course, the various dimensions of poverty often go together.

-Reeves, Rodrigue & Kneebone

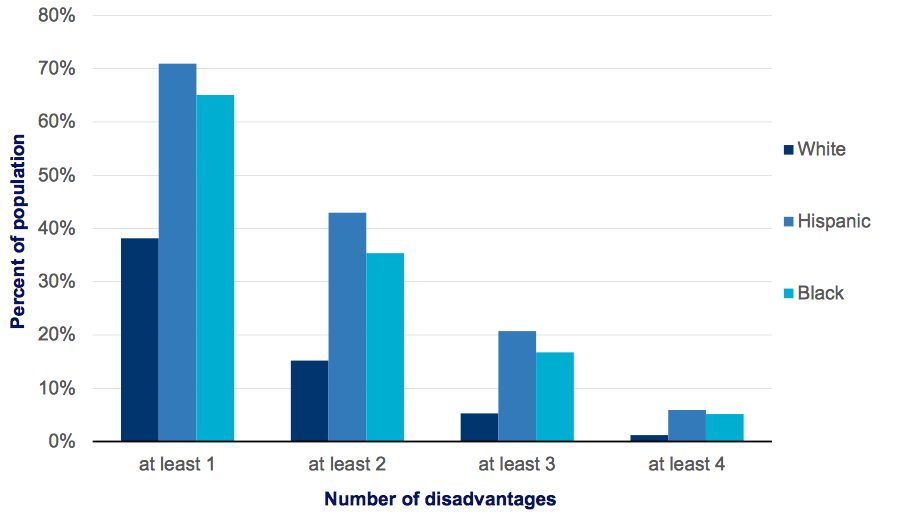

The study samples adults aged 25 to 61 to find out how many fell below the threshold for each of the five evils of poverty. On a positive note, data shows that while half of adults face at least one disadvantage, only a small percentage of the group felt the effects of “cluster poverty” (two or more disadvantages).

However, data shows that blacks and Hispanics who are effected by one aspect of poverty are also much more likely than their white counterparts to be effected by another.

With each additional dimension, the relative risk for blacks and Hispanics rises by roughly a factor of one. Compared to whites, blacks and Hispanics are twice as likely to be disadvantaged on at least two dimensions; more than three times as likely to be disadvantaged on at least three dimensions; and more than four times as likely to be disadvantaged on at least four dimensions. Blacks and Hispanics are more likely to experience disadvantages piling on top of each other.

The authors argue in favor of policies that de-couple low-income from other dimensions of poverty, in addition to those that reduce overall the various dimensions of poverty, quoting Jonathan Wolff and Avner de-Shalit’s book Disadvantage: “A society of equals is a society in which disadvantages do not cluster, a society where there is no clear answer to the question of who is the worst off.”

Click here for more quick reads featuring interesting articles on philanthropy and impact investing.

Comments are closed here.